I have a song stuck in my head, and soon you will too. Smooth Operator by Sade. It’s not a new song, it was released back in the eighties, but it’s a good one. It’s the one I often hum to myself when I’ve had, or witnessed, an especially awesome math moment.

This began a few years back during my first year as a math coach. I had the pleasure of working at Brookside Junior High for a coaching block of 6 weeks. One day in class a student offered a particularly cool, unexpected, and streamlined solution to a math problem. I was pretty impressed and said as much to the teacher, Mr. Josh McNeil, who remarked, “yeah – she’s one smooth operator”. Well one thing led to another and before long the class was singing along to Smooth Operator blasting through the sound system as we continued to compare solutions and methods. I loved that moment, and I think of it often. Students got the message that there are multiple paths to a solution. If you tune into the particular numbers in the question, you may even find something really slick – an efficient or interesting strategy that makes use of the relationships between the numbers in the problem.

So what’s got me singing Smooth Operator today? Well I just participated in Pam Harris’ MathStratChat on Twitter. If you haven’t participated before – what are you waiting for? Solving the problem is secondary to sharing and discussing interesting methods. The tagline: Be clever. Be original. Be inspired.

Obviously – I love it.

The question that has me jazzed today? 121 – 77. A fairly simple problem to be sure, but what would you do? Or maybe I should ask, what would you do if this was THE problem …the ONLY problem …not one of 25 similar problems where the goal is the successful repetition of a given algorithm. When I saw this prompt, my first instinct was to use the fact that both numbers in the problem had 11 as a factor.

My thinking: 11 elevens – 7 elevens is 4 elevens. And 4 elevens is 44. Once I had my solution, I scrolled through the thread to view the other strategies participants shared. I saw cool ideas I hadn’t thought of and noticed how those who shared my thinking recorded their thoughts. Follow this link to check it out!

Fun conversation right?

As an educator immersed in the middle school crowd, I reflected on the ways I bring this focus into the classroom. How do I make time to play with different strategies, persist when the first one doesn’t pan out, and prove by making strategies visible so they can be shared and tested with a community of learners? Would my students have the diversity of methods to make this exercise fun? Would they appreciate seeing lots of ways to solve a problem? Would they be giving off the content, smooth operator vibes that I am right now? If not, why not?

Too often teachers skip the play-around-with-numbers exercises in favor of showing students how to solve problems using one method that works every time. Instead of students testing, comparing, discussing, and deciding for themselves what method matches their thinking and what method may work well and why, they are programmed to stop thinking and just do. Subtraction problem? Well stack them up and subtract right to left! Don’t forget to line up according to place value! Be careful of regrouping! Now do 25 more to make sure it is so automatic you don’t even have to think about it!

Yikes. No thanks.

Yes we will get answers. Yes, this method may work every time. But come on!

Where’s the creativity, efficiency and fun? And perhaps more importantly, will students remember, internalize, and be able to use methods effectively long term when they don’t really know how or why they work? Will students recognize when to use certain operations in problem solving scenarios when the only meaning they attach to an operation is a list of steps to follow? Will students use an algorithm every time even when other methods may be more efficient? Will students be unwilling or unable to even attempt a question since they’ve received the message that only one way is the right way and they forget that particular right way? As teachers, can we find time to explore different paths to the answer so students can tune into, make sense of, extend and consolidate mathematical ideas they already have and compare them with methods their classmates suggest? Can we build confidence, efficiency, accuracy and flexibility while still valuing individual thinking and reasoning?

How can we change our focus from trying to build human calculators to celebrating smooth operators?

Last year I was a guest in a classroom where students were operating with fractions. I was surprised to discover that many of the computational errors came from subtraction. Not subtraction with fractions, just subtraction. The work from earlier grades just didn’t land with some of these students. All were using the subtraction algorithm in the margins of their work every time subtraction arose – no other strategies. I could see errors with regrouping that weren’t noticed by students. Opportunities to add on or create an equivalent and simpler problem were largely ignored. They had one subtraction strategy and when they couldn’t execute it correctly there was no back up plan. Beyond that, students lacked strategies to confirm accuracy. In chatting with one student I confessed that I wasn’t a fan of regrouping. In fact, I confided, I often go out of my way to avoid it. One method that works well for me is creating an equivalent problem by adding the same amount to both the subtrahend and minuend. This is a compensation strategy that makes use of the idea that maintaining a common difference can be used to create an equivalent problem with the same result. For example, the question 92 – 37 can be rewritten as 95 – 40. A quick change that creates a problem that I can do easier in my head by avoiding any errors related to regrouping.

“You can do that?!?” the student asked. She was amazed and excited, but also a little put out that she had been operating all this time without this valuable information. “What should we test to make sure that we can?” was my reply.

After a few tests using different sets of numbers, this strategy was accepted as valid. We started with some whole number examples then tried some examples with mixed numbers just to confirm that this method can extend to different number domains. Then we discussed when this idea would be useful. Making the strategy visible using a number line model helped us verify that we could use it anytime but it was especially useful to avoid regrouping. Later I overheard this same student sharing her new strategy with a classmate. Yup…she was giving off some smooth operator vibes!

We did take a sideroad that was not part of the plan for the day. But this conversation helped with solving accurately and efficiently and it improved this student’s flexibility. Sooooooo worth the side trip! But when do or should these conversations happen? Is this a whole class or small group discussion? Do these strategies need to be taught and practiced in isolation? When can I make time for this in my jam-packed schedule?

One thing I have noticed over the years is that the opportunity to inject some smooth operating comes up all the time. Just ask as often as possible, “How did you figure that out?” and “Did anyone use a different method?” and “I wonder if there is another way to think about this?” You will be amazed at the variety of strategies you hear. Just asking these questions on a regular basis prompts students to think why, and how, and what if. Resist the urge to show and replace it with a desire to know what your students think. Then, if you notice, like I did, a group of students blindly calculating with minimal reasoning, you can supplement your work with focused investigations that involve discussion, value creativity, and promote knowledge of the operations beyond algorithms.

So where to begin? How can you dip your toe in the smooth operating pond, early in the school year with a diverse group of learners? Is it possible to meet all students where they are and engage in meaningful discussions if students aren’t used to thinking beyond some given steps? Yes! But what if you have a class with a range of needs, strengths and experiences? Still yes! My favorite activity to kick things off is Number of the Day. Not only does this routine serve as a jumping off point for noticing patterns and regularities for different operations, it is naturally differentiated so every learner can participate at an appropriate level of challenge. This routine involves giving all students the same number. Say…5. Their job? Write as many problems as they can with this number as the solution. (Maybe I should be calling this Solution of the Day.) You can hear more about this warm-up idea by checking out my video presentation on warm-ups found here. Using a routine like this can help you notice what students record, what computations they are comfortable with and which they avoid. Once the allotted time is up, I ask for examples and record student responses they volunteer on the board for all to see. This is when the magic happens. Being intentional about how you record responses allows patterns to be noticed. Then, a general wondering like, “ohhhh…I see a pattern here! Can anyone describe it? extend it?” can get a great discussion going. I facilitate the recording of a regularity and work to extend and test the generalization. Depending on how the conversation goes, I may ease into a discussion about strategies. Depending on the group of students, this may be the work of one class period or perhaps several sessions over the course of a week. Then in future classes, I can highlight moments in our regular classwork where the opportunity to use our strategy shows up. With the particular class mentioned earlier I might focus on subtraction. In the class I’ve been working with recently, I think multiplication and division might be the focus.

Recently in class, this group of grade 8 students were noticing things about perfect squares. We created lists of factors to show that in perfect squares, there is always an odd number of factors where the lonely one in the middle is the square root. We also created factor trees for numbers and noticed that only the prime factorizations of perfect squares can be arranged to create two identical groups with one of these two identical groups being the square root. This work differs from the work of the previous class since we are not really exploring an operation. But here, multiplication and division strategies are assumed and required. So what happens when students lack the flexibility to select and apply strategies that would prove useful handling such investigations? What do you do when some students have strategies to generate a factor list and others have none at all? Could this be an opportunity to identify and build smooth operators?

Creating a list of factors for a number can involve a whole slew of strategies. Think about it. If I am finding the factors of 90, as students were doing that day in class, what knowledge of numbers and patterns do you put to use? Take a moment to try it yourself. What reasoning and strategies do you use? How do you record the factors you find? How would you approach leading this task in your classroom?

When I create a list of factors for a number I record factor pairs in increasing order. I’d start with 1 and 90 as the outer boundaries of my horizontal list, leaving a space in the middle for the rest. I continue to test consecutive numbers and record factor pairs in order until I meet in the middle. This strategy keeps me from missing a pair. But that is just the start of the strategies. I use patterns in my list, I half and double, I think of divisibility rules, I break up the dividend to divide, I think of partial quotients…

There’s a lot of reasoning happening. This is an opportunity to tune into strategies. A chance to build number sense and flexibility. This is a moment for some smooth operating!

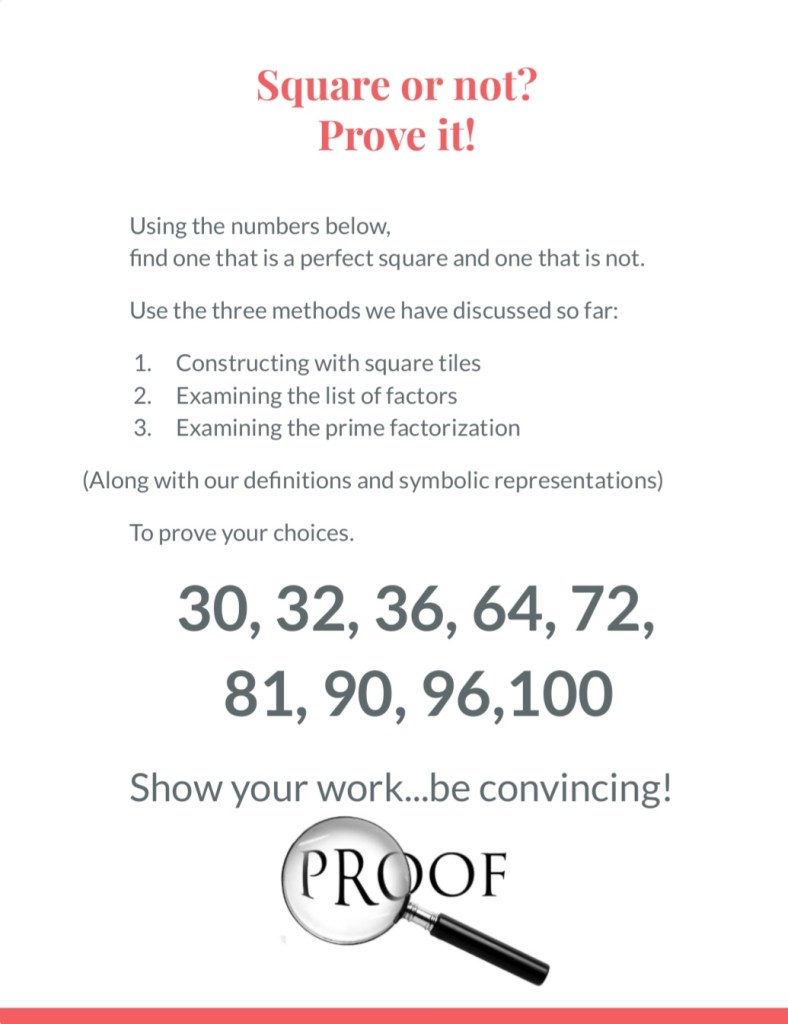

Students were working on the assignment Square or Not? Prove it! pictured below.

This task is simple enough if you can get that list of factors. But creating that list was difficult for some. How do you talk through the multiplication/division connection with students? What happens when students depend on a multiplication chart and the chart does not extend far enough?

I had so many different and individual conversations in that class about multiplication, division, and patterns that connect them. But at the end of the day, I wasn’t sure that anything really stuck. Would students be able to apply or reason through this work without my prompting? If given a new number, would they be able to apply this reasoning independently? We needed further investigating, modeling, and discussion to solidify some basics, but could use a method to fall back on while the work of building our skills continued. Since we were also making use of the prime factorizations of numbers in this assignment, I thought connecting this to the list of factors might be helpful. Students were successful with finding the prime factorization of numbers since identifying two factors of a number is all you need to start a factor tree. Finding factors of these factors is then easier since the numbers get smaller as you go. Once the prime factorization is found, a list of factors can be made by using all combinations that can be made with these prime numbers. This method helped students in the moment. But our work with dividing is far from over.

In the coming weeks, we will work on some dividing concepts in our warm-ups. Sometimes the questions will be directly connected to our class work like list all the factors of 144. And our goal will be to max out discussions on different methods, patterning and thinking that lead to a complete list. Other times we might ask a true or false question like, if 12 is a factor of 144, then all the factors of 12 are also factors of 144. True or false? Questions like this can prompt testing and consolidating in students that may not have tuned in yet to why a factor tree can help with finding a list of factors. Hopefully it will also open up a variety of ways to record ideas, test generalizations, and confirm accuracy. We might also pose a prompt like this inspired by the work of Pam Harris:

12 x 12 = 3 x ?

Here we’d want students to use relationships to reason through to an answer (not compute) and we’d try to maximize discussions and use models to make relationships concrete and visible. All of these prompts are getting at the same ideas, but by asking questions in different ways and looking for responses that go beyond a numerical answer we are building mathematicians that wonder, relate, explain and defend.

So where do these ideas come from for creating smooth operators?

Well truthfully, at the start of my career, I tried drilling algorithms when multiplying and dividing skills in students weren’t what I needed them to be for grade level work. (CRINGE) I can confirm that this does not work. Even when students can successfully work their way through a long division problem, or rhyme off their multiplication facts, it rarely translates to recognizing when or how to use these skills in a problem and hardly ever helps students notice connections and patterns. When I found myself with students that needed interventions, and discovered that shutting down class for a few days to drill algorithms was clearly not an appropriate response, I had to learn some strategies myself. I also had to really tune into what strategies I used, when and why. I rarely use long division personally. So why would I suggest it to my students to find their factor list? I realized that in the absence of solid reflection on how I tackled a problem, my reflex was to teach it the way I was taught. If you are teaching in the middle grades, you may find yourself in a similar situation. How do students learn multiplication and division when the latest research on how, when, and why is put to good use? Do you know how students learn multiplication and division these days? Do you have division strategies beyond long division? Have you thought about how you would record those ideas so that your thinking is visible and understandable? Are you as smooth as you think you are when it comes to operating?

Well a few years back I wasn’t. I didn’t know the latest methods for teaching and learning the basics. When students came to me without grade level prerequisites I panicked. My response? Extra homework! Help at lunch time! Drill math facts! Send them off to the resource teacher! All just a series of band aids for the real issues. Yes, students needed work with strategies. But I needed this work too. This is confirmed for me regularly when Pam Harris’ MathStratChat involves division. The strategies other participants share are cool, efficient, and sometimes new to me. Or their method of making their thinking visible is new to me. I have been in this business a while and I still have lots of work to do. In addition, once I recognized that being a smooth operator and building smooth operators were related but different, I knew I had to push myself further.

My work with cohort 7, led by Virginia Bastable and others at Mount Holyoke College, was a significant mile marker in my fluency journey. The student thinking assignments I completed as part of my masters program certainly helped me focus on tuning into what students say and building gradually on their ideas. Check out these books below for ideas, examples, videos, and step-by-step lessons for focusing on patterns in and connections between operations.

But if a masters program is not something you can commit to at the moment, there are other ways to begin your fluency journey. Talk to elementary teachers, math support teachers, and elementary math coaches about their strategies. These methods may be new to you and discussing them together may give you some insight into the prior learning of your students. It may surprise you how much you can learn. In addition, check out the work in the amazing resources pictured below. If you are a teacher in the Halifax Regional Centre for Education, these books are likely in your school already! Work on fluency with your students. Define what fluency means for you and compare that view to the related research contained in these pages. Think about the areas of challenge for you and your group of students and look for ways to address it. Test out the games, activities, and prompts. These books contain ready-to-use materials to support this work.

But more than anything else, think about what changes you can make to your practice so that you can highlight smooth operators. For me, this meant I had to listen more and speak less. I needed fewer examples but ones chosen or crafted with more intentionality. I needed to go beyond answer-getting and explore the many paths to a solution. I had to prioritize conversations that explore the efficiency of methods and how efficiency is impacted by the numbers in the problem. I had to confirm when and why certain ideas worked and make those relationships concrete by using models. I needed to think about what prior knowledge my students needed for grade level concepts and explore how those concepts are currently taught. And I needed to do more math myself. Engage with Pam Harris’ MathStratChat, and play, persist and prove as many ways as you can! If your journey is anything like mine, before long you and your class will be humming along to Smooth Operator too. And yes…as you might expect, that vibe is cool, chill, satisfying and sweet!

spectacular! Reports Highlight [Social Justice Movements] and Their Impact 2025 marvelous

LikeLike

Thank you for your comment!

LikeLike